Welcome to the club no one wants to be in. Spinal disc injuries are very (very) prevalent, with as many as 20 case per 1000 adults annually. Lumbar disc injuries are the most common, followed by cervical disc injuries. The majority of these cases are injury based, with only 5% being attributed to degenerative disc disease. This month, we’ll explore the anatomy of the spine, break down how disc injuries occur, and share the latest research on recovery.

Back injuries can feel overwhelming. Understanding the structures involved, how they function normally and how they can become dysfunctional, can help focus your rehabilitation goals.

There are 23 discs in the human spine: 6 in the cervical region (neck), 12 in the thoracic region (mid-back), and 5 in the lumbar region (lower back). Each intervertebral disc (IVD) lies between two adjacent vertebrae in the spinal column, allowing the spine to be flexible without sacrificing a great deal of strength. They also provide a shock-absorbing effect within the spine and prevent the vertebrae from grinding together.

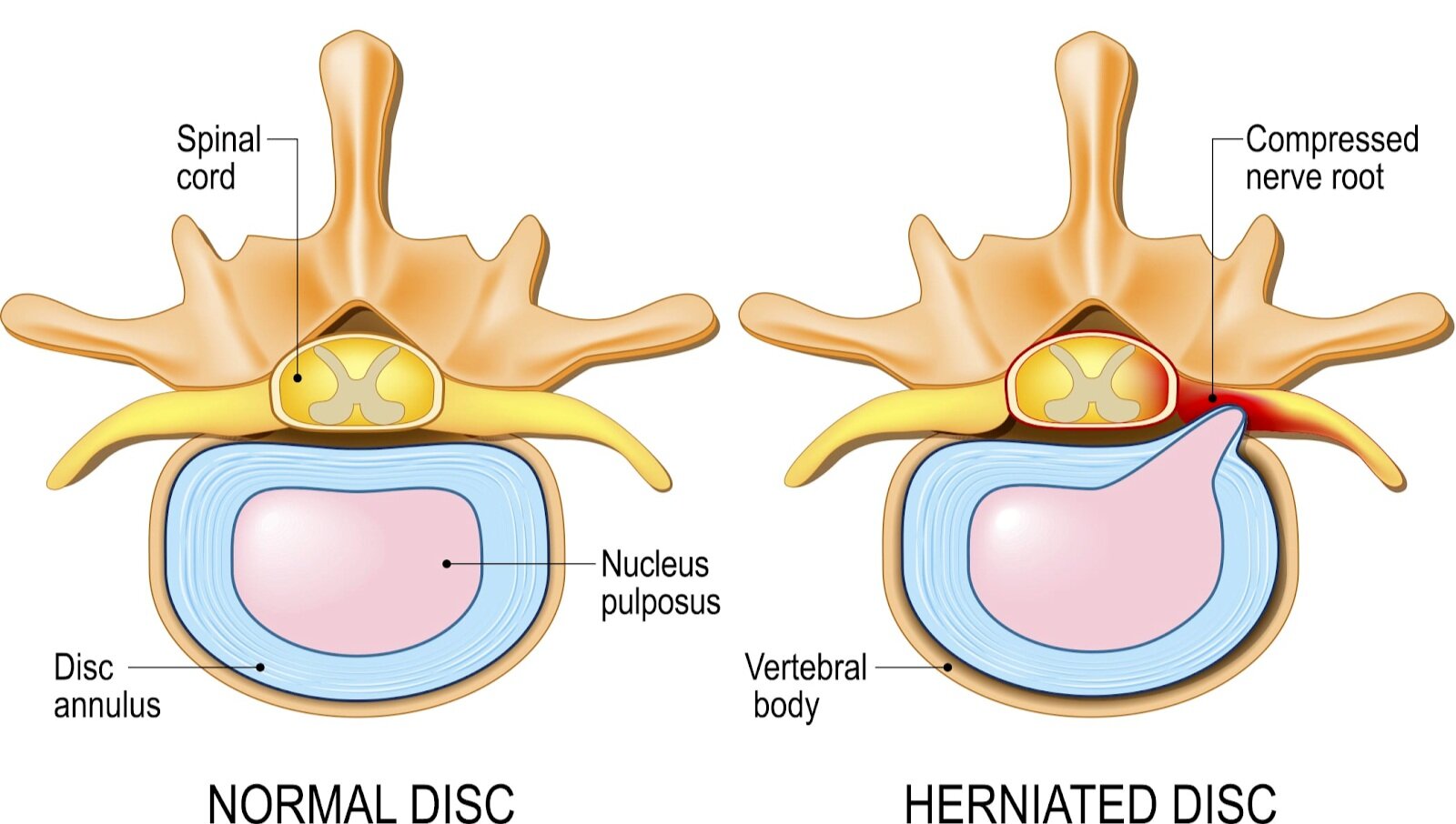

They consist of three major components: the core, nucleus pulposus (NP), the outer ring, annulus fibrosus (AF) and the cartilaginous endplates that anchor the discs to adjacent vertebrae.

So why does it hurt so much, and how does this even happen?!

Disc “bulge”, “protrusion”, “herniation”, even “slipped disc”, as well as disc degeneration all refer to interruption of the normal disc anatomy. Damage to the outer ring, or AF, can occur from sudden trauma to the disc or from disc degeneration due to age and repetitive use. Without the structure of the AF, the NP can be displaced.

While the discs are designed to move to counter spinal movement, repetitive asymmetric compressive loading isn’t ideal. For example, during forward bending, or flexion of the lumbar spine, the NP migrates posteriorly or backwards. Conversely, the nucleus is squeezed anteriorly or forwards during backwards bending, or extension of the lumbar spine. Adding extra weight to one of these positions over and over can cause injury. Research shows the damage to the AF appears to be associated with fully flexing the spine for a repeated or prolonged period of time.

Like everything else, our Intervertebral discs age. The NP shrinks as it’s gelatinous material becomes dries out over time and is replaced with fibrotic tissue. This places increased strain on the AF. The resulting flattened disc reduces mobility and may impinge on spinal nerves leading to pain and weakness

Due to the proximity of the disc to the spinal cord, if the disc extends beyond its normal resting position, it can result in pain. This pain is due to a combination of the mechanical compression of the adjacent nerve by the bulging NP and localized inflammation and swelling. The symptoms you experience are dictated by what nerves are irritated. Nerve compression can often cause radiculopathy - or radiating symptoms along the path of the compressed nerve into the legs and feet.

To learn more, check out these articles:

Waxenbaum JA, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Intervertebral Discs. InStatPearls [Internet] 2018 Dec 13. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470583/ (last accessed 27.1.2020)

Dulebohn SC, Massa RN, Mesfin FB. Disc Herniation.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441822/ (last accessed 25.1.2020)

L. G. F. Giles, K. P. Singer. The Clinical Anatomy and Management of Back Pain. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006.